Myths are True

Apollo's mother, Leto, didn't give birth in a nice hospital surrounded by

helpful nurses. She was being chased by Python, a huge snake intend on

harassing her. So Apollo was born with a chip on his shoulder and something

to prove.

When Python caught sight of Apollo intent on revenge, he took off and hid

in his temple at Delphi. But Apollo followed him into the shrine, and

despatched him and his wife, Delphyne. Mother Earth reported the sin to

Zeus, who made Apollo repent and organize the Pythian Games.

Robert Graves, and other mythologists, looks at stories like this in a

historical context that recounts an invasion of Northern Hellenists into

Central Greece and the Peloponnese, who captured the land and their shrines

and converted them to their man, Apollo. To placate the masses there,

"regular funeral games were instituted in honour of the dead hero Python,

and his priestess was retained in office." [Greek Myths, page 80]

While this is one approach to myth interpretation, it personally doesn't do

much for me. I prefer to take a more poetic view. For instance, creation

stories don't just try to explain the origin of the natural world, but also

of the inner world.

We are each born into a paradisiacal garden of ignorance. Our all-knowing

father takes care of us and we feel we are immortal and can't die. We don't

even know of the concept of death. But then this serpent show up (and

you'll notice the phallic imagery that refers to puberty) and talks us into

growing up and learning about the ways of adulthood. No longer innocent and

being great know-it-alls, we are kicked out of our father's house and

cursed to work and sweat like an adult.

We each begin immortal and innocent, but we each personally fall, and it is

stories like this that try to bring our personal experience into the

collective experience, and to try to make sense of it. We each fall, but

why? Can we ever regain the sweetness and purity of youth? Or are we

forever doom for knowing too much?

Natalie Baan, in her article in the latest issue of Parabola,

The Woman in Chains, gives this sort of poetic light to the popular Greek

story of Perseus and Andromeda. If you can't remember the story, here

is a brief synopsis…

Perseus is tricked into attempting to kill the Medusa, the monster that was

so horrific that anyone that looked on her was petrified. Along the way, he

meets Athena who gives him a helmet that makes him invisible, Hermes'

winged flying shoes, and some other tools and information to help him lop

off the monster's head.

After completing his task,

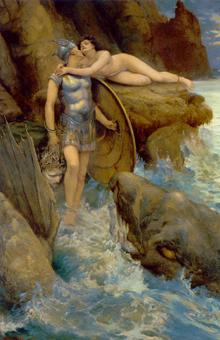

If you feel that the story of Perseus and Andromeda is a bit sexist, you might enjoy this painting that flips things around a bit.

he's flying home with the head in his backpack

when he sees a naked woman chained to some rocks on the beach. Like any

other boy, he stops for a better view. He then notices a large sea monster

heading for shore, and then he starts to ask questions.

He tells her that he'll save her if she'll agree to be his loot… er,

wife, and she agrees. He pulls out the head from the backpack and turns the

monster to stone. And with a brief exception at the wedding party, they

live happily ever after.

How do you view this story poetically? We need to start by looking at the

symbols and realizing that each character is some part of our self. We

sometimes feel trapped and vulnerable (naked and chained) and being ravaged

by inner turmoil. The sea, in Jungian dream interpretation, is looked at as

a symbol for the subconscious, and sea monsters are those primal, beastly

issues that sabotage our life (our country).

But just as we are about to submit to despair, a disembodied voice calls to

us from sky. The sky, or the heavens, is viewed as the realm of the

super-conscious, but feel free to insert your own label, be it God, our

higher self, enlightenment, etc.

The Call will save us if we will offer ourselves in marriage. Marriage too,

is a symbol in many early religions and cultures, as the union of flesh and

spirit… the call to a "spiritual life." You will see this symbol in

Gnostic writings as well as the poems of Rumi, etc.

Now maybe you can see why I can say that myths are true.

The other day, I had a conversation with a friend of mine as to whether the

people of ancient cultures consciously worked these symbols into their

stories … or whether eggheads like myself, were just reading more into

them. I personally think that the coincidences are too great to simply

dismiss, but if you get something out of it, what does it matter?

Tell others about this article: