Replace Shell Pipes in Emacs

An Itch

Don’t misunderstand. I may be an Emacsian, but like you, I’m also a polyglot and spend time every day in remote shells and REPLs. However, I have an itch that I’ve been scratching, and while I haven’t reached any endorphin rush, I thought I would share an idea to start a bit of a discussion.

How would you solve the following challenge:

Read a file of text, determine the n most frequently used words, and print out a sorted list of those words along with their frequencies.

Yeah, you may recognize the origin of this question, and you might quickly bang out this answer:

tr -cs A-Za-z '\n' | tr A-Z a-z | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | sed ${1}q

But one does not just cast a spell of that wizardry level on the first try. Instead we iterate over each command, pipe by pipe. Nothing wrong with this…unless the first step doesn’t come from a file, but from a command that takes a bit of time.

The other day, I was looking for an image on our cloud system, and I didn’t

know its name. Since I had suspicions, I issued calls to openstack and started

piping to grep. However, let me illustrate the problem:

$ time openstack image list | wc -l 2404 real 0m51.432s user 0m2.895s sys 0m0.156s

With a couple thousand images in one cluster, an openstack command may

takes almost a minute to complete. A challenge to iterate since the

command can’t be memoized. The immediate solution is to write that to a

temporary file, and begin grepping on that.

I have another solution (obviously, using Emacs), but humor me with another story that prompted the solution.

The Prompt

Last week, I noticed that Planet Emacsen referenced an Irreal article that was particularly not Emacs-centric, Text Manipulation with Command Line Utilities:

If your computing experience has always involved GUI tools, you may be unfamiliar or rusty with the command line tools that Unix provides. Similarly, if, like me, you do almost all your text manipulation from within Emacs, you might also be rusty with the command line tools. Happily, Kade Killary has a solution.

Killary has a very useful post entitled Command Line Tricks for Data Scientists that discusses those tools and how to use them…

The article starts:

For many data scientists, data manipulation begins and ends with Pandas or the Tidyverse. In theory, there is nothing wrong with this notion. It is, after all, why these tools exist in the first place. Yet, these options can often be overkill for simple tasks like delimiter conversion. Aspiring to master the command line should be on every developer’s list, especially data scientists. Learning the ins and outs of your shell will undeniably make you more productive.

My personal problem is I remember the command line utilities and forget the often better and easier approach to just use Emacs.

Usually I won’t think, start a terminal tab, kick off the openstack command

with a pipe for further processing, and then curse after a minute waiting for

the results, without remembering that shell-command (either C-x ! or SPC !)

will put the output of the command in a buffer (named *Shell Command Output*),1

allowing me to repeatedly call the keep-lines and flush-lines commands until I

have what I want.

Using Emacs is especially nice with these time-consuming commands, since automatically putting the output in a buffer is essentially memoizing the call.

Map of Unix Tool to Emacs Function

The article covers the following tools, and I’m appending a similar Emacs command. However, even without functional equivalents, I could simply shell out to the particular command:

- Iconv

set-buffer-file-coding-system(C-x <Return> f)- Head

- n/a, try

narrow-to-region(C-x n n) - Tr

vr/replace/downcase-region- Wc

count-words(M-=)- Split

- n/a as Emacs now handles this automatically.

- Sort & Uniq

sort-lines/ delete-duplicate-lines (or Spacemacs’uniquify-lines).- Cut

- this is useful, but I don’t know of anything similar in Emacsland.

- Paste

- combining two files (no, not appending, more like zipping) is a highly specific use case.

- Join

- like a text-oriented sql from text files that I have never used, mostly due to the lack of properly formatted files.

- Grep

keep-lines/flush-lines- Sed

vr/replace- Awk

- Emacs Lisp ;-)

After going through the list, I realize that there are a couple of features

that without shelling out to the command, would probably require a quick

macro, and run apply-macro-to-region-lines (C-x C-k r). However, cut is

pretty useful from parsing CSVs or tabular output, and it wouldn’t be too

difficult (and fun) to write a version in Lisp.

However, many of these commands actually don’t have a keybinding, since they

aren’t used much, and I’m afraid I don’t always remember the function names.

Perhaps it might be nice to have a minor-mode that could be hooked to

shell-command output buffer with single keys to various functions, but perhaps

I’m getting ahead of myself…

Pipe Replacement

The first command function that seems useful would be a replacement for the

shell’s pipe. Essentially, we’d take the contents of a buffer, send it to a

command, and replace the buffer’s contents with the output from the command.

Let’s get highly creative, and call it pipe:

(defun pipe (command) "Replaces the contents of the buffer with the output from the command given." (interactive "sCommand: ") (let ((current-prefix-arg '(4))) (shell-command-on-region (point-min) (point-max) command)))

Setting the current-prefix-arg variable like that fakes out Emacs’ interactive

system to make the function believe the user pressed C-u before calling the

function, which replaces the contents of the buffer with the output from the

command.

Let me try it, by running the shell-command and typing openstack server

list…

Oh yeah, I need to set up my environment variables. Since I work with more

than one cluster, I stored those in files that I call source. Might be fun to

hack a Lisp function that reads a file into a temporary buffer, searches the

buffer for KEY=VALUE pairs, and calls setenv on each:

(defun source-environment (file) "Add all environment variable settings from a script file into the current Emacs environment, via the `setenv' function." (interactive "fSource file:") (save-excursion (with-temp-buffer (insert-file-contents file) ;; This hairy regular expression matches KEY=VALUE shell expressions: (while (re-search-forward "\\([A-z_]*\\) *= *[\"']?\\(.*?\\)[\"']?$" nil t) (let* ((key (match-string 1)) (env-value (match-string 2)) ;; Since the value could contain references to other environment ;; variables, we'll try to substitute what we find: (value (replace-regexp-in-string "${?\\([A-z_]*\\)}?" (lambda (p) (getenv (match-string 1 p))) env-value t))) (setenv key value) (message "Stored environment variable %s = %s" key value))))))

[ After jamming that function out, I noticed someone had already made a project to do just this. ]

Now calling the command brings up a buffer, *Shell Command Output* with the

output from the command:

+---------------------------------+------------------------+--------+------------------------+---------------------+ | ID | Name | Status | Networks | Image Name | +---------------------------------+------------------------+--------+------------------------+---------------------+ | b0f1916f-c6ee-460f-ae2a-b89dcf6 | wpc-tempest | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.51 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | e2a4e57e-9c3f-4e67-84c3-ef0f2f1 | wpc-infrastructure-3 | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.52 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | e83cde9d-8c10-4877-81ba-bbee901 | wpc-infrastructure-1 | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.53 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | 419bf293-4d65-4bb7-88e4-5adcfb6 | network-controller-1 | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.54 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | 3fa945e9-6d62-496e-9779-7ab2841 | wpc-compute | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.55 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | e47aaa36-380b-4cc0-9695-cf8b605 | wpc-controller-1 | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.56 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | 3e69fc6e-48fc-4f41-9f46-47f9668 | wpc-infrastructure-2 | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.57 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | 250f6a42-1a88-40c0-a075-2338f51 | wpc-network-analytics | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.58 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | ad430c07-403e-417b-8ac4-d73adfb | wpc-load-balancer-1 | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.59 | c7_inf_base_0.22.15 | | 157a06c0-f442-4647-b50b-34df9b3 | wpc4-chef-server | ACTIVE | cedev13=192.168.146.60 | wpc4-chef-server | +---------------------------------+------------------------+--------+------------------------+---------------------+

If I wanted to get the IP address of each of my virtual machines, I could

begin by calling flush-lines with a parameter of --- to remove all the

table separator lines. Of course, that doesn’t get rid of the header row, but

deleting a single line is easy enough (Actually, I should have just called

keep-lines with a parameter of ACTIVE since that seems to be common text on

each line).

Now let’s try my new function. I call pipe with a command parameter of cut -d= -f2

and then call it again with cut -d' ' -f1 and I’m left with a buffer of IP

addresses. I’m intrigued with this workflow.

As a work in progress, check out these new functions here.

Piper Mode

With a couple of functions scoped out, let’s figure out a way to easily present and use them.

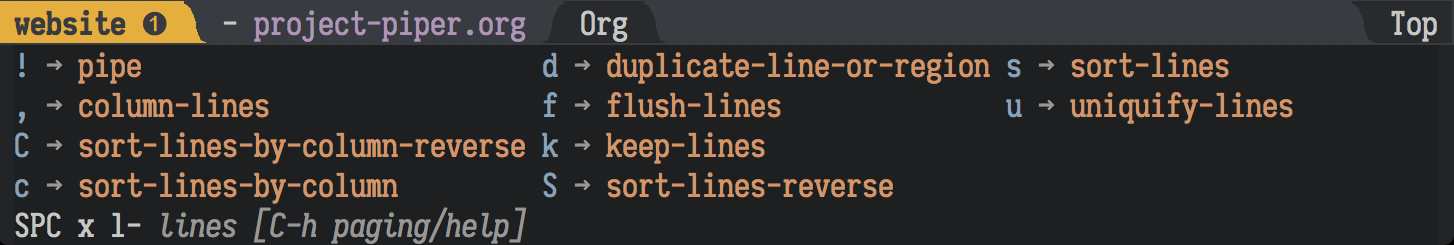

Suppose we had a minor-mode that gets instantiated with the shell output

buffer, and it has a single key-binding, the vertical bar key, |, that shows

either a magit-popup buffer or a hydra with these emacs-equivalent

command-functions. Since we might still want to have normal navigation and

editing capability in the buffer, we should make few special bindings beyond

what the Fundamental major mode provides.

(defvar piper-mode-map (let ((map (make-sparse-keymap))) (define-key map (kbd "<SPC>") 'scroll-up-command) (define-key map (kbd "<DEL>") 'scroll-down-command) (define-key map (kbd "C-|") 'piper-popup) map) "Keymap for `piper-mode'.") (define-minor-mode piper-mode "Toggle Filtering mode." ;; The initial value. :init-value nil ;; The indicator for the mode line. :lighter " |" ;; The minor mode bindings. :keymap piper-mode-map :group 'piper) (add-to-list 'emulation-mode-map-alists `((piper-mode . ,piper-mode-map))) ;; if using Evil-ness, simply do this: (define-key evil-normal-state-map (kbd "|") 'piper-popup) (magit-define-popup piper-popup "Show popup buffer featuring shell-like piper commands." 'piper-commands :actions '((?f "Flush" flush-lines) (?k "Keep" keep-lines) (?c "Cut Columns" columns-lines) (?s "Sort" sort-lines) (?u "Unique Lines" uniquify-lines) (?! "Next Pipe" pipe)) :default-action 'pipe)

Getting the details correct is left as an exercise to the Reader, and I am currently months into my experiment with Spacemacs.

With Spacemacs, this is much simpler, especially since many of these sorts

of commands are bound to the prefix, SPC x l (for text lines), so, in order

to sort the buffer, type: SPC x l s, and to reverse sort it, SPC u SPC x l s,

which may seem like a lot of typing, but SPC u is Evil’s way of doing the

prefix (C-u). Let’s do more:

(spacemacs/set-leader-keys "x l !" 'pipe) (spacemacs/set-leader-keys "x l f" 'flush-lines) (spacemacs/set-leader-keys "x l k" 'keep-lines)

Grab my current bindings here.

Summary

In discussing this with Ken, he made the astute observation that instead of manipulating flat textual data, the first step should be to parse and render the data into an data structure within Emacs Lisp, and then transform and filter the data using normal programming techniques.

If the parsing is trivial, this makes perfect sense, as filtering with Dash’s

-filter function is far preferable to grep. The openstack CLI has a little

known option, --format, for spitting out parseable data in JSON and other

formats, but I perhaps Ken is correct when he wrote to me:

inspired by the R statistical language, which possesses sophisticated facilities for transforming input data into R’s canonical data structure representation, then operates on that data structure until it produces a result. R deliberately distinguishes the ingestion, processing, and presentation phases, which is a useful mental model for what you hope to accomplish…

What approach would be less effort and greater reward in the long run? How much developer effort would be expended writing library code for each phase in order to parse it with a real language? It might be a significant challenge to build abstractions for handling the myriad text formats we encounter day-to-day, but would that be more effort than wiring together sequences of shell tool equivalents for each text format?

…I see a lot of value in a library that could intelligently parse common tabular data into an S-expression. OpenStack’s table format, for example, is an elaborate variation on CSV and it’s worth evaluating whether an extension to csv.el could close the gap.

Converting shell output formatted as a table into a list of lists data structure, is pretty trivial:

(defun table-to-lists (delimiter &optional trim) "Converts the contents of the buffer (or a region) into a list of lists where each line should be separated by DELIMITER. If TRIM to `t', each column element is trimmed of whitespace." (let ((start (if (region-active-p) (region-beginning) (point-min))) (end (if (region-active-p) (region-end) (point-max)))) (mapcar (lambda (line) (split-string line delimiter nil trim)) (split-string (buffer-substring-no-properties start end) "\n"))))

For the command line tools we use daily, creating these sorts of converters could be a big advantage, and in that case, the literate programming concepts I’ve described before, could really be helpful.

However, this essay is a workflow enhancement to general (almost single-use) commands. Clearly, this is also an experiment, as I’m not sure if I will actually finish this. However, I’m intrigued with this new workflow and would love to discuss these ideas.

Footnotes:

While calling shell-command always puts the output in this *Shell Command

Output* buffer, it only displays this buffer automatically if the output is

large. After running the command, simply switch-buffer to it.

Note: If you ran the command in a subprocess asychronously (either by appending

an & character, or by calling async-shell-command), the output will be held in

a different buffer, called *Async Shell Command*.