Literate DevOps

((tl;dr See my video presentation/demonstration of this essay))

Maintaining servers falls into two phases:

- Bang head until server works

- Capture effort into some automation tool like Puppet or Chef.

Recently, I’ve been playing around with making the first phase closer to the second. For lack of a better word, I’m calling it literate devops.

I’ve talked about using org-mode’s literate programming model to investigate new ideas and crystallize thoughts, and this approach appears to work well for me since I lack those esoteric sysadmin skills.

Tell us a Story

Once upon a time, I was tasked with patching an RPM, which is not in my comfort zone, so my initial plan of attack was:

- Use Vagrant to create a disposable CentOS system

- SSH into this virtual machine to download needed tools

- Run various unknown commands

- Rinse and repeat this step until successful

Of course, once I figure out the solution, I need to document it for others on my team, and maybe create a repeatable script.

First step is well documented elsewhere, but today I learned (TIL)

you can ssh directly to your Vagrant-based virtual machine with

this little magic (Note: client is the name of my virtual

machine I specified in the Vagrantfile):

vagrant ssh-config --host clientvm >> $HOME/.ssh/config

This command appends some lovely host-connection magic so you can

issue: ssh clientvm

Literate Devops

Instead of opening up a terminal to my virtual machine, I pop into Emacs and load this sprint’s note file1, create a new header, and enter the shell and ruby commands in this text file.

What good is this? Unlike a traditional terminal, this allows me to log, document and execute each command.

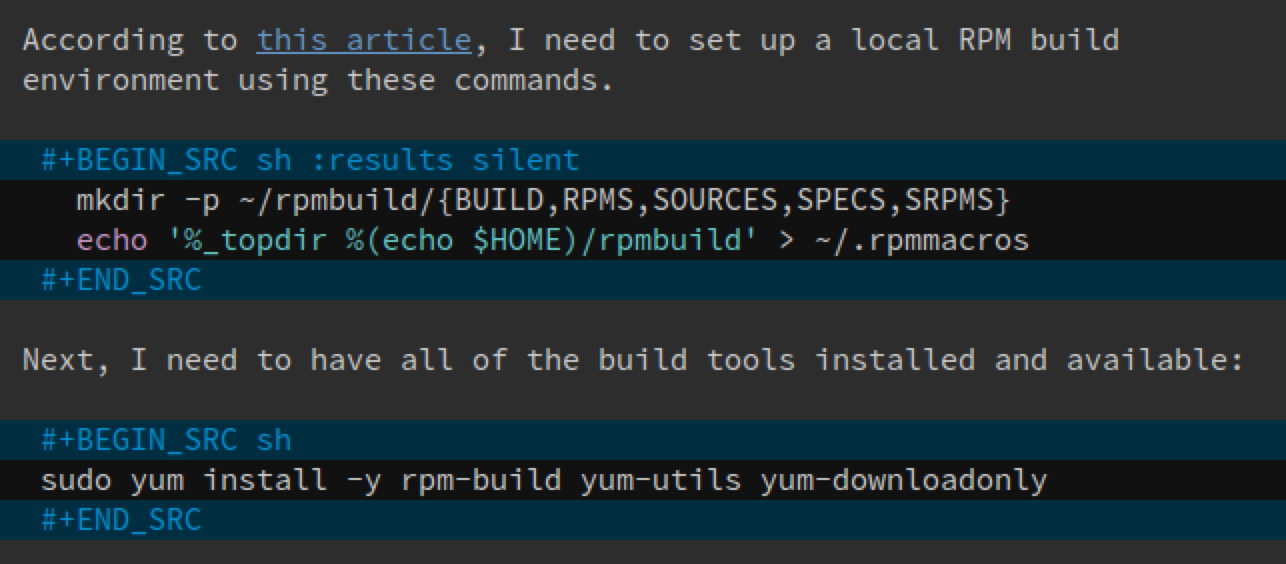

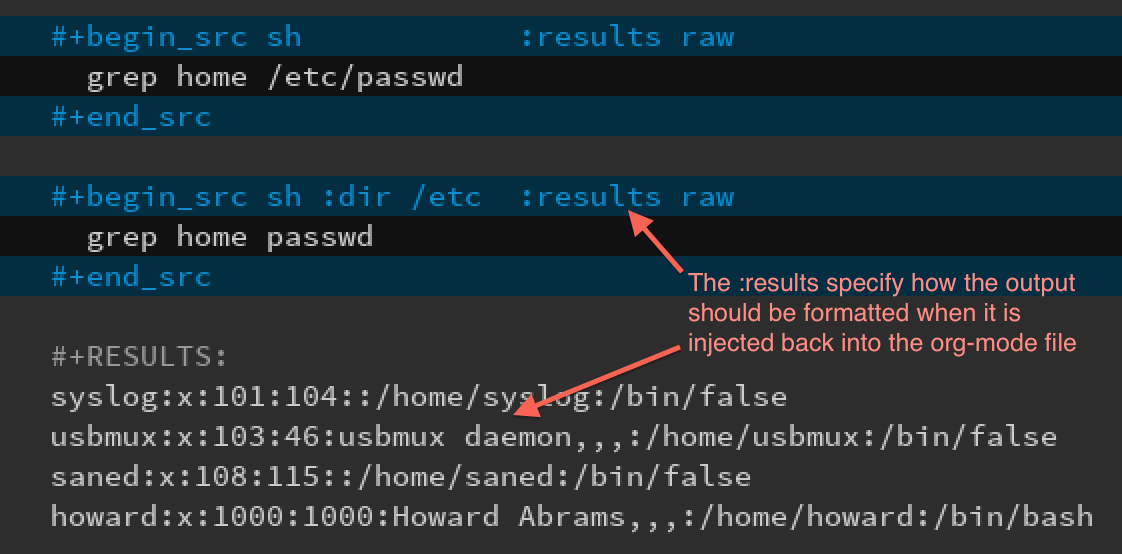

For instance, here is a screen-shot of a section of my Emacs buffer:

As an old bear with very little brains, my prose can explain the background and purpose of each command. Clicking the hyperlink refreshes my memory of previous discoveries. A keychord executes the code block…

Yes. I execute the commands from within Emacs.

Hitting C-c C-c (Control-C twice) runs the code (based on the

language). This example runs in the shell. The results are placed

back into the file, which can be used by other code blocks (and many

other options).

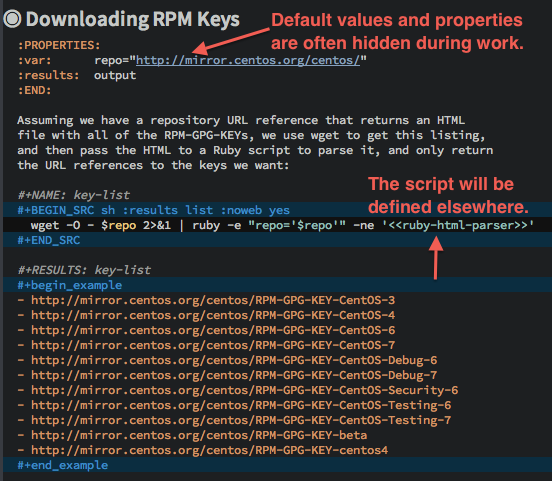

For instance, here is the first half of a section for downloading the GPG Keys from a repository (the URL is placed in a property that is shared among all code blocks in his section):

The Shell script block (in the center of the screen-shot) uses

wget to download the HTML index file and parse and extract the key

file URLs. We’ll have a Ruby script do that parsing, and since the

script may be a bit hairy, we’ll define it in another code block.

One technique from literate programming is the idea that one code

block can be inserted into another block (the reference is a name

within double angle brackets, <<...>>). Donald Knuth called this

feature WEB. Since it can accidentally conflict with some languages

(like Ruby), I have it off by default, but turn it on for this block

with the noweb parameter.

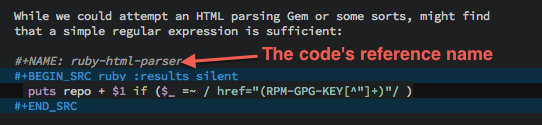

Here is the Ruby script. Having it in a separate Ruby-specific code block allows me to turn on all the Ruby magic that Emacs can muster.

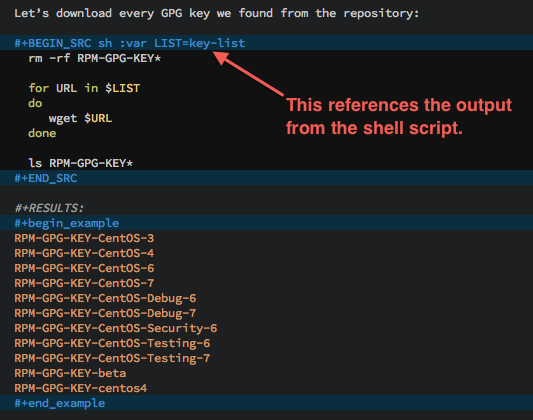

The last step is to take the URLs produced by the first script and

feed them to another Shell script that will call wget to download

each:

The key-list was the name of our original code block, as well as

the name of its results. We assign that list of results to a

variable, LIST that the shell script would access as $LIST.

This example demonstrated how literate programming can weave code and data through different languages.

What about the Virtual Machine?

Normally, specifying sh as the code block’s language, tells

Emacs to run the code in my local system’s shell, but in this case,

I want it ran on my virtual machine (or on my development server in

my lab). I’ll describe two options for doing this, using Tramp and

Babel Sessions.

Tramp to the Rescue

Tramp is an Emacs feature that allows one to edit a file on a

remote machine using ssh and other protocols. For instance,

running the find-file function (bound to C-x C-f) lets you type

something like:

/ssh:howard.abrams@goblin.howardism.org:web/files/robot.txt

If you put the following in your .emacs initialization file:

(setq tramp-default-method "ssh")

And update your ~/.ssh/config file to know what user account goes

with the host name, the file reference above can be shorten to:

/goblin.howardism.org:web/files/robot.txt

Emacs looks for the : character to determine if Tramp should be

invoked. Tramp uses SSH keys if available, or will prompt you for

a password if needed.

Each org-mode code block can specify a :dir option that specifies

where the code snippet should run, for instance, the following

blocks are equivalent:

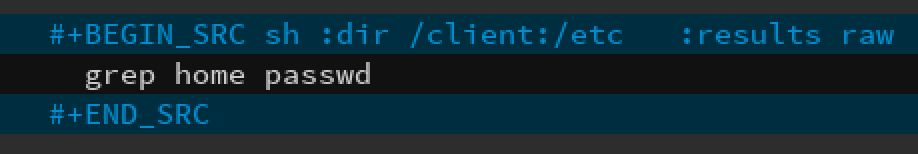

The :dir option allows full Tramp functionality, allowing me to

run a block on a different machine. Remember how I added my

client Vagrant virtual machine to my ~/.ssh/config file?

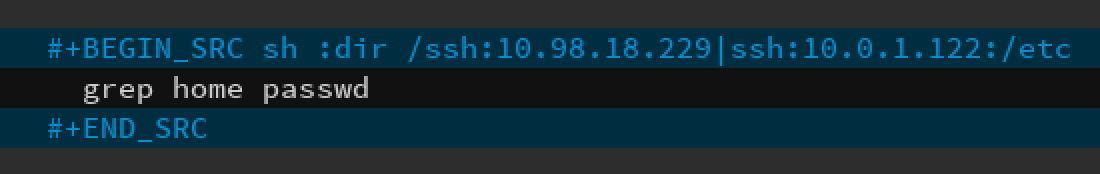

But I need access to my machine behind a firewall!?

My job deals with virtual machines running in a highly protected data center, where I need to first log into jump boxes and bastion machines. Tramp handles these sorts of hops. For instance:

/ssh:10.98.18.229|ssh:10.0.1.122|sudo:/etc/network/interfaces

Uses my account name to log into the bastion machine, and

then uses my account name to ssh into a virtual machine running

in a private cloud. And then uses the sudo command to let me edit

a file owned by root.

Tramp pipe references works with the :dir option for org-mode

source blocks:

Few tricks to keep in mind:

- All but the last hop uses a pipe character, |, instead of the colon character, :

- If you use the pipe character, you need to specify all

protocols, like

ssh, even if it is the default. - If your local machine’s operating system is different than the

machine you are connecting to, you need to fix a bug in

org-mode, which I can show you how to fix2.

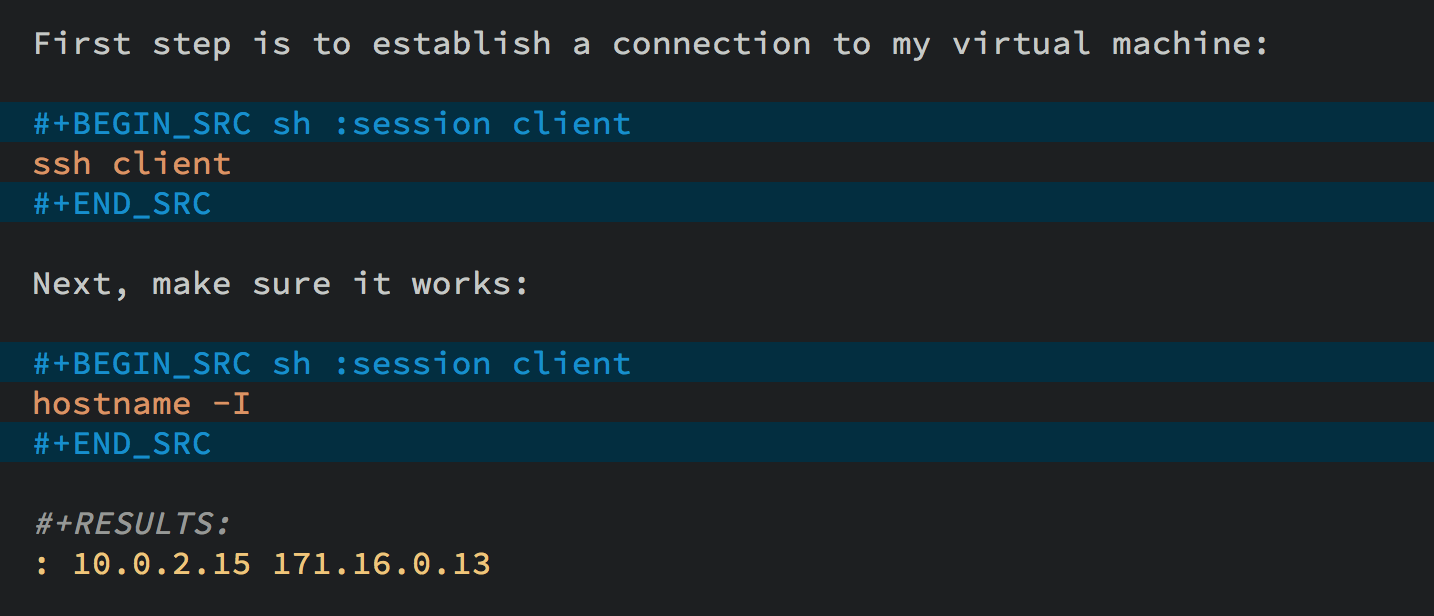

Using org-mode Sessions

Another approach is to create a session that connects different

code blocks together. Each screen shot below, each code block below

has the same session value, client (which is conveniently the

same my virtual machine’s hostname, client):

If I execute the first block, a shell is started in the

background, and it ssh’s into the machine. Note, to get this

working, you need to enable password-less access by placing your

SSH’s public key into the remote system’s .ssh/authorized_keys

file, or using the ssh Emacs package.3

From this point on, each code block I execute with the client

session value, uses this connection, and the code is executed on the

remote machine (a virtual machine in this case, but that doesn’t

matter).

Either of these approaches works well, but the second approach, allows me to set variables to create a particular state that other blocks may expect. However, this requires execution of each block in order.

I have a third, more interactive, approach4 using screen, but

it doesn’t allow passing variables to the code, and as you’ll see

below, this is pretty important to me.

Regardless, I continue learning how to accomplish my goal, all the while documenting and validating my steps. The end result can be exported to web or wiki page.

What about Verbose Commands?

Yes, executing some commands can be quite time-consuming and verbose, but often I need to search the results, and having the results placed in an Emacs buffer allows better searching.

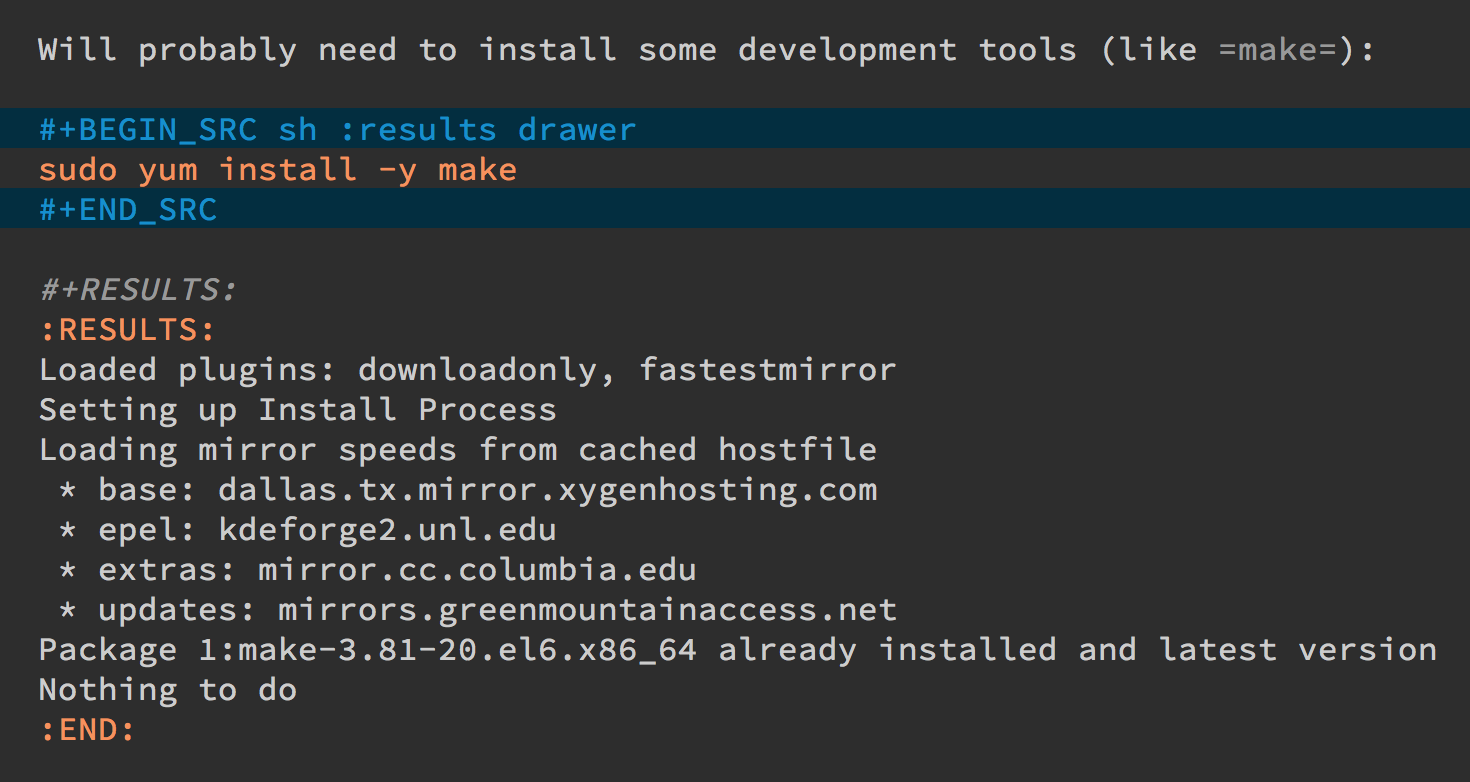

Often I use a collapsible “drawer” (which is just a way to identify the beginning and end of the output):

Place the cursor on this drawer and hit the Tab key to hide or

show the output:

Can you Use the Output?

The results of some commands are often needed for the next command, and I’m sure you just love using your mouse to copy and paste part of the output, but I have a better way.

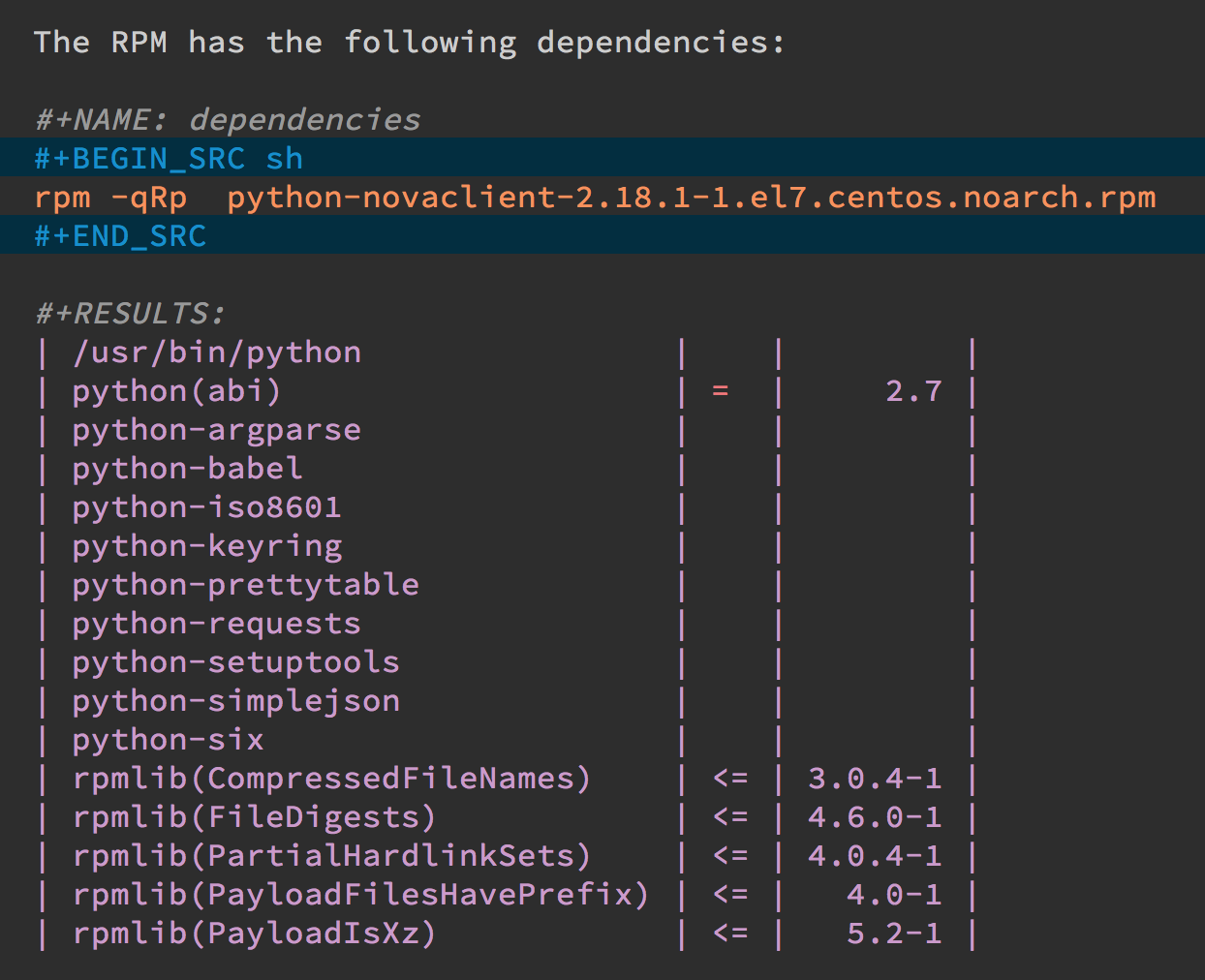

For instance, I needed a list of an RPM’s dependencies:

Notice I named this source code block. Also notice how Emacs automatically broke the results up into a table. By default, the output from shell commands are split along newlines and spaces.

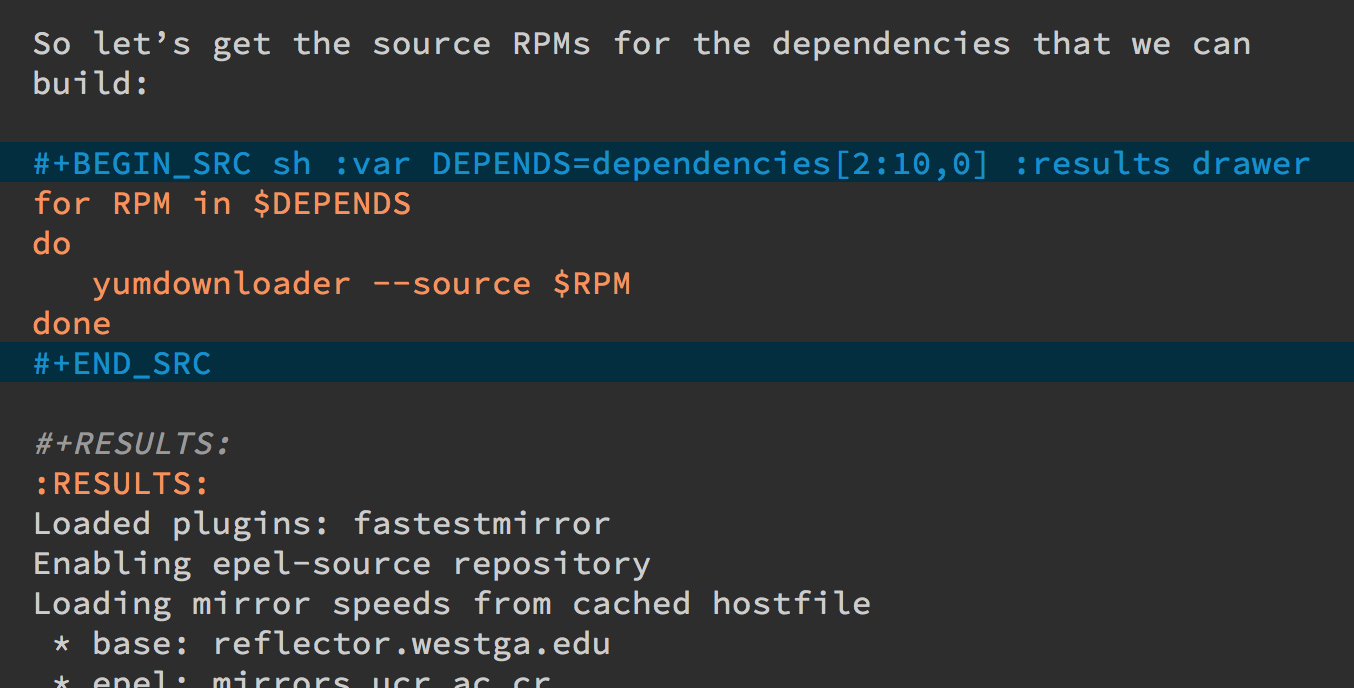

I can feed the results of these execution to another code block.

The following source block creates a variable named DEPENDS that

uses rows 2 through 10 of the first column as an array.

I then download the RPMs I want without any mouse interaction.

Setting Variables and Values

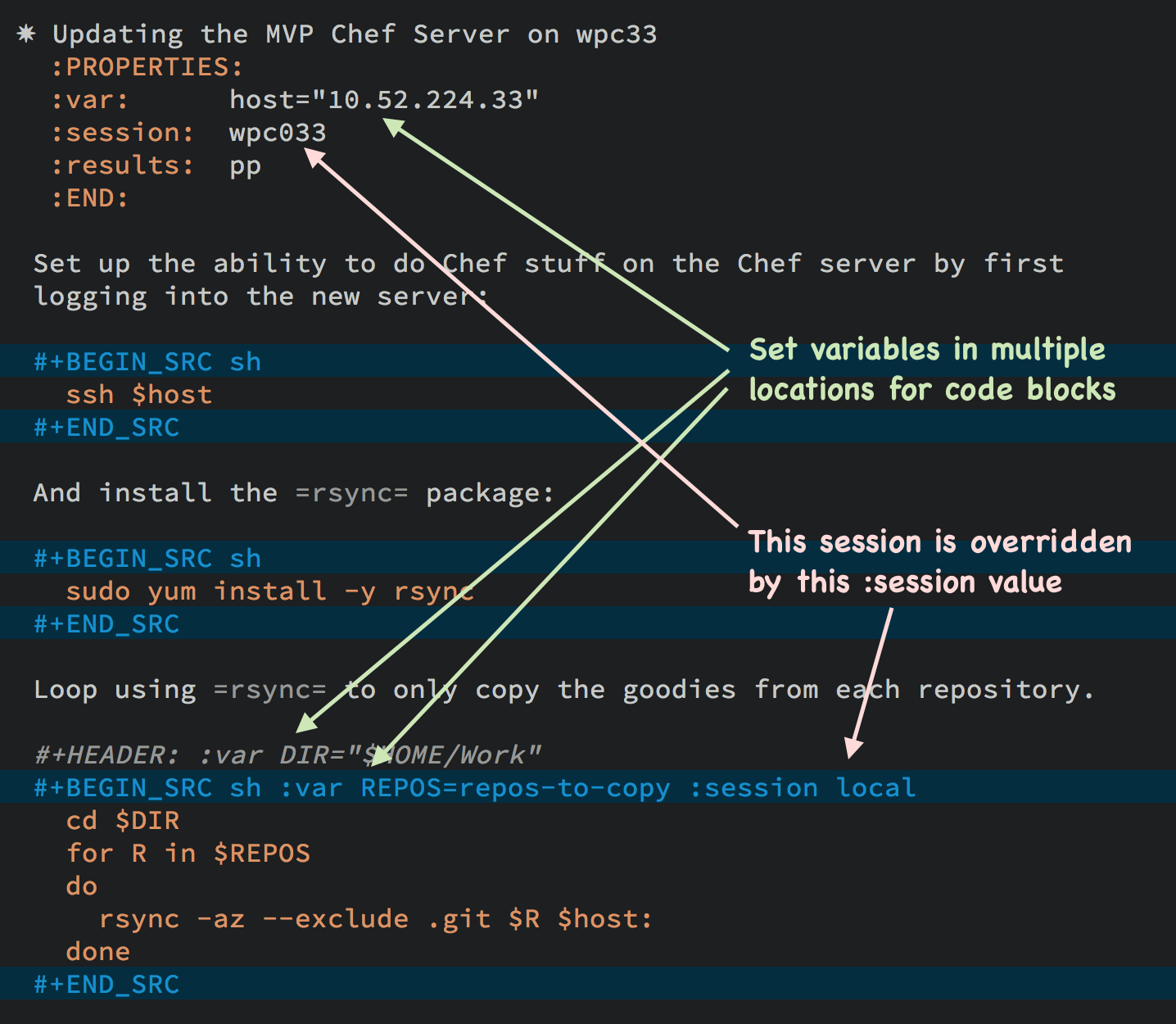

A key aspect of reusing devops programs (like a Chef cookbooks) is the separation of the code from the values the code uses…a key aspect of any program you reuse.

In my world, I create a new org-mode file for each sprint, and

each task or problem gets its own header and section. Each section

can have a drawer of properties, including variables shared among

all code blocks in that section.

To create a section variable, simply hit: C-c C-x p, and set the

Property to var and the value to a variable=value, as in:

host="10.52.224.33"

This drawer can contain any code block values you wish, like

session or results. These values can then be overridden as

settings on the code block, as you see in this screen-shot:

Setting variables and settings (especially the session setting),

ties the code blocks together.

Communicating with Others

While investigations in operations and administrations (as I’ve

described) are useful to oneself when understanding the problem

domain, I need to communicate the results with my team mates.

Since my Emacs configuration allows me to send mail messages, I kick

off the function, org-mime-org-buffer-htmlize, which exports the

org-mode file to an HTML mail message (This function is part of

the latest org-plus-contrib package).

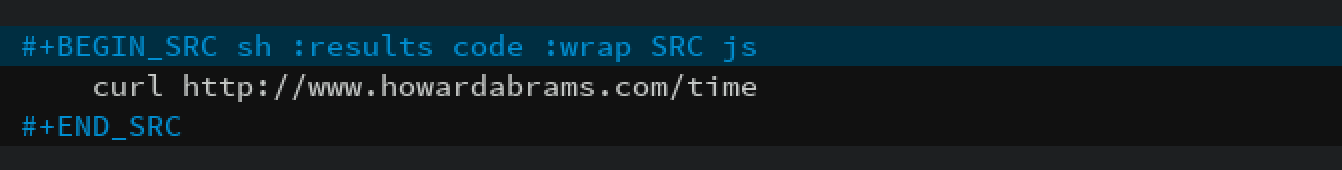

However, some times the exported results are not quite perfect.

For instance, some blocks may result in some JSON data, and since

the HTML output can colorize the syntax, if I could just specify

that the output results were JavaScript, then the JSON data would be

much prettier. Just use the wrap parameter, as in:

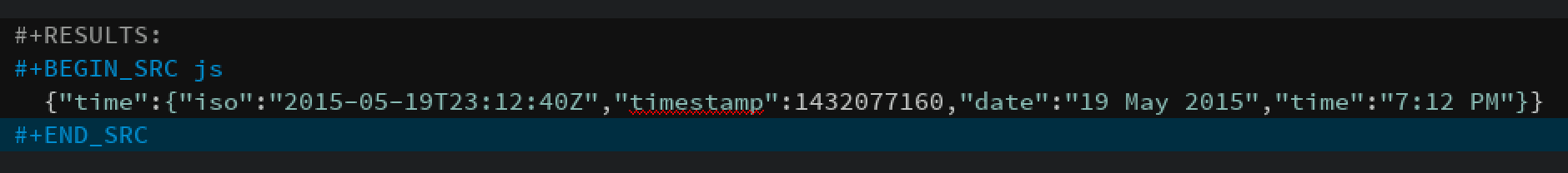

Which puts the following in my org-mode file:

Which gets exported like:

{"time":{"iso":"2015-05-19T23:12:40Z","timestamp":1432077160,"date":"19 May 2015","time":"7:12 PM"}}

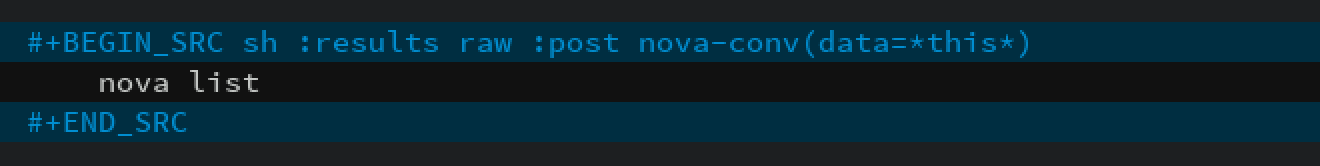

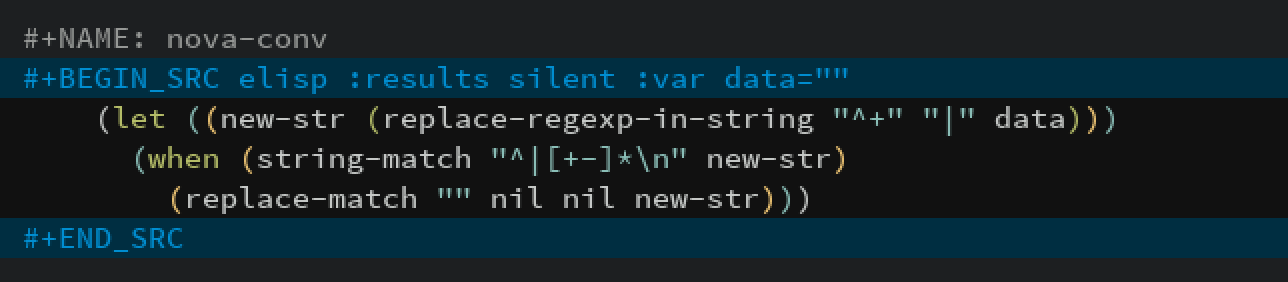

For another example, my current project involves working with OpenStack,

and its nova command line utility attempts to format the data as a

table:

+--------------------------------------+--------------------+--------+------------+-------------+------------------------+ | ID | Name | Status | Task State | Power State | Networks | +--------------------------------------+--------------------+--------+------------+-------------+------------------------+ | f9e7aed8-e425-4808-aace-8758dadd91bf | chefserver | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.73 | | 0432f8b1-7e6d-4fc1-b181-02fa768c38ac | ha-compute1 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.104 | | a5bdd1d0-d4b3-4856-a657-5759356c186b | ha-controller1 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.97 | | 16263972-609e-44c0-83e0-f3147336071c | ha-controller2 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.99 | | 89a89d1f-7be5-4c4f-82db-64b751f15f3b | ha-controller3 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.100 | | b740095a-3f89-45d0-a2a1-9cfcadfb4ca3 | ha-monitoring | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.95 | | 6bebe823-1504-4cb1-a898-bbc7894b1a32 | ha-sdn-controller1 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.101 | | 456bf417-580e-49fb-be08-1b0153710f86 | ha-sdn-controller2 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.102 | | 7aab184c-5fb4-4996-8ab2-8a65ea7668cb | ha-sdn-controller3 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.103 | | 0c90d7b0-dab4-4af8-a970-e2e90dd8b9e4 | ha-storage-1 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.76 | | fda0666e-d656-48fd-928f-83fb47c923f2 | ha-storage-2 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.81 | | 021fc9c1-8d79-4c09-b3d4-6014d242403a | ha-storage-3 | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.96 | | bc5ad0fe-9ef2-4966-8d2b-99892f3f94cd | yum-server | ACTIVE | - | Running | WPC-private=10.0.1.74 | +--------------------------------------+--------------------+--------+------------+-------------+------------------------+

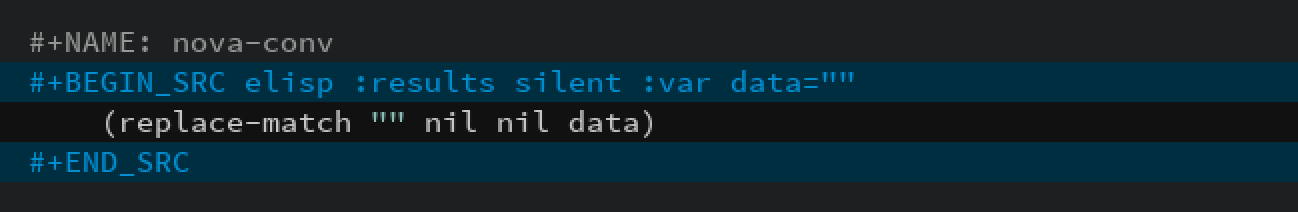

If you manually change the output, those changes will not be honored when the file is exported (since those are redone during the exporting process).

The way to do that is with a little Emacs Lisp code block that you just need to place somewhere in your file, like:

With this code block named, nova-conv, I can use it to

post-process the results, as in:

In my particular case, I also want to get rid of that first line of

dashes to make it more org-mode like:

To be truly re-useable, place this code in your Library of Babel, and then it is available from any file.

Summary

While my literate devops approach shouldn’t replace real DevOps (OpsDev?) automation, I have found this approach useful for two reasons:

- As a good way to take notes before writing a cookbook.

- As an easy approach to compose emails to teammates when stuck.

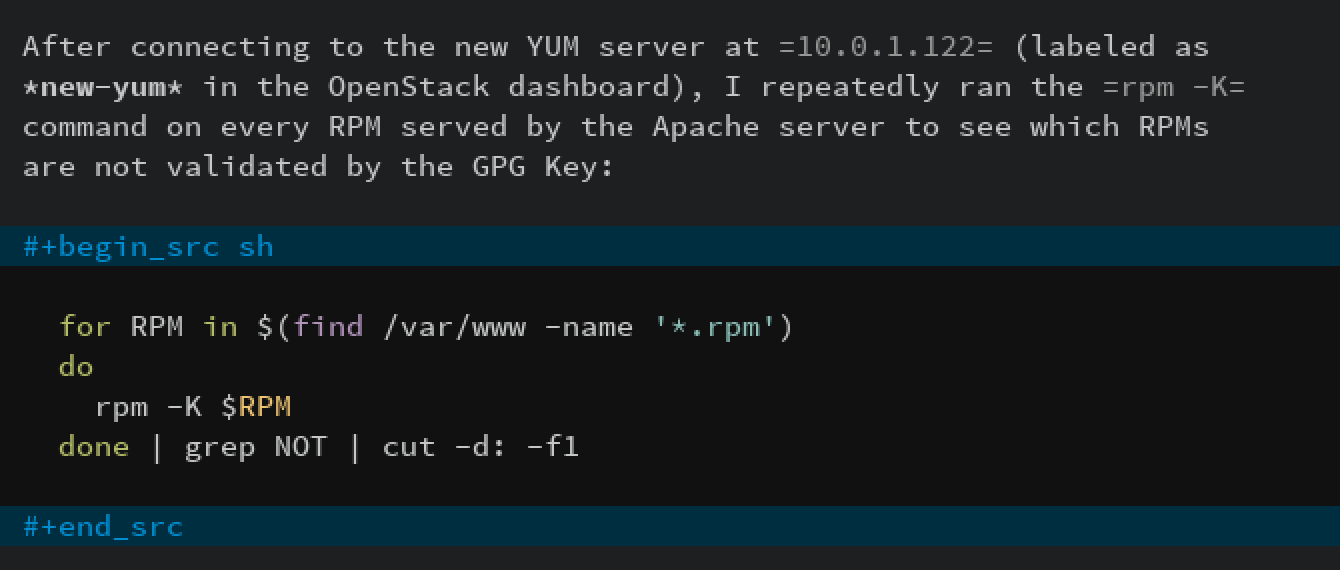

Regarding the last point, I often write my literate files in the past tense, even before I write and execute the code, as in:

Then, if the command or process I’m following fails, I can simply

high-light a section of my document, hit C-x M to email an

exported HTML version to the rest of the team (otherwise, I’d

spend hours copy/pasting back from the terminal in order to provide

sufficient context for the email).

Need a complete example? Check out my notes on setting up IP Tables (and the original org-mode file), where part of the file can be executed in the editor in order to see how my machines are configured, and the other part is a script that can be tangled to a machine and executed to reset to the firewall rules.

Thanks for reading.

Footnotes:

For each new sprint, I create an org-mode formatted file to keep track of tasks, notes, and other details. This makes it ideal for embedding a bit of literate devops.

Every operating system creates temporary files in different

directory locations. Most Unix systems, use /tmp/, but Macs use

/var/folders/. The current org-mode code uses the same directory

name on the remote system that would work on the local system. In my

case, I’m using my Mac laptop at work to connect to a Linux system in

my data center, and I get the following error:

Tramp: Decoding remote file `/ssh:x.y.z:/var/folders/0s/pcrc3rq5075gj4tm90pbh76c36sl1h/T/ob-input-32379ujY' using `base64 -d -i >%s'...failed byte-code: Couldn't write region to `/ssh:x.y.z:/var/folders/0s/pcrc3rq5075gj4tm90pbh76c36sl1h/T/ob-input-32379ujY', decode using `base64 -d -i >%s' failed

The bug is in org-mode version 8.2.10 (and probably earlier), as I

found in this mailing list posting (and it may not be fixed for a

while since it isn’t real clear what the best solution would be). To

fix it yourself, edit ob-core.el file in the org-babel-temp-file

function to be:

(defun org-babel-temp-file (prefix &optional suffix) "Create a temporary file in the `org-babel-temporary-directory'. Passes PREFIX and SUFFIX directly to `make-temp-file' with the value of `temporary-file-directory' temporarily set to the value of `org-babel-temporary-directory'." (if (file-remote-p default-directory) (let ((prefix ;; We cannot use `temporary-file-directory' as local part ;; on the remote host, because it might be another OS ;; there. So we assume "/tmp", which ought to exist on ;; relevant architectures. (concat (file-remote-p default-directory) ;; REPLACE temporary-file-directory with /tmp: (expand-file-name prefix "/tmp/")))) (make-temp-file prefix nil suffix)) (let ((temporary-file-directory (or (and (boundp 'org-babel-temporary-directory) (file-exists-p org-babel-temporary-directory) org-babel-temporary-directory) temporary-file-directory))) (make-temp-file prefix nil suffix))))

If you install the ssh.el project, you would initially connect

to your remote system using: M-x ssh

You would then enter the host connection information, including the

password (if needed), etc. For instance, if I connected to my host:

goblin.howardism.org, then my code blocks would refer to a

session like this:

#+begin_src sh :session *ssh goblin.howardism.org* :var dir="/opt" ls $dir #+end_src

This is allows you to watch your code execute on the remote system, but still allow a fully functional code blocks that can read values from other parts of the org-mode file.

Note: The value to the session parameter is surrounded by *

characters (part of the buffer name), but the variables you

want to pass in are surrounded by quotes (otherwise, they are

interpreted as named references to tables elsewhere in the document).

I have a third way of executing remote commands, and this uses

the ob-screen extension (located in the org-mode Contrib

collection). It uses both Gnu screen and xterm, so on my Mac, I

start XQuartz (the built-in X Windows emulator), and add the

following to my .emacs initialization (based on these instructions)

to set the full path to my xterm program:

(setq org-babel-default-header-args:screen '((:results . "silent") (:session . "default") (:cmd . "bash") (:terminal . "/opt/X11/bin/xterm")))

I don’t often use screen, but I install using Homebrew:

brew install screen

And then tell ob-screen how to find it:

(setq org-babel-screen-location "/usr/local/bin/screen")

The code blocks are now specified as screen, and I typically specify

which xterm window to use by setting the :session parameter:

#+BEGIN_SRC screen :session blah ls /Applications #+END_SRC

The results do not get placed into my Emacs file buffer, but are

simply left, as is, in the xterm window.

The other down-side to using screen is it doesn’t pass in

variables. For instance, the following doesn’t work:

#+begin_src screen :session blah :var dir="/Applications" ls $dir #+end_src

Seeing the back-and-forth results in the xterm window is nice, but

not being able to bring the results back into the file for further

processing is limited. Also, you must resist the temptation to fix a

command by typing in the xterm window. If you go down that path, you

may forget to put that information back into your org-mode file, and

may regret it later.